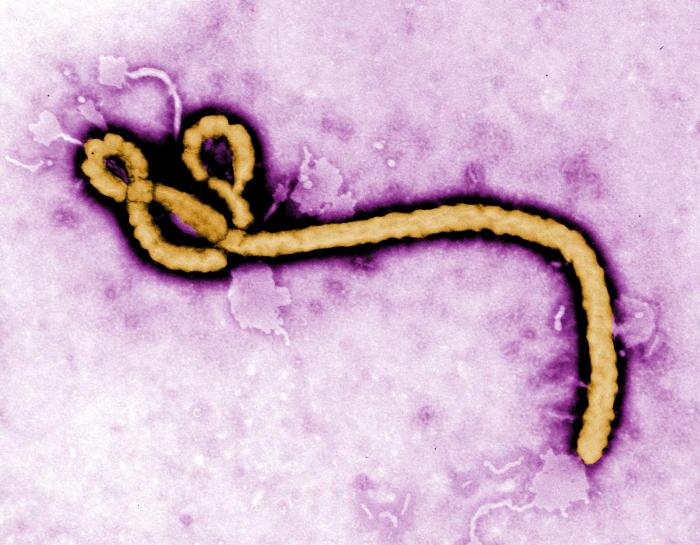

Ebola virus and Marburg virus are both highly contagious filoviruses and are among the most lethal viruses known. Patient deaths are often a consequence of gastrointestinal damage leading to diarrhea and severe dehydration. A team from Boston University (BU) aimed to elucidate the mechanisms behind how these viruses impact the gastrointestinal tract.

The findings were published in PLOS Pathogens in a paper titled, “Filovirus Infection disrupts epithelial barrier function and ion transport in human iPSC-derived gut organoids.”

Using induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), the researchers created organoids mimicking intestinal and colonic tissues. The authors wrote, “Our iPSC-derived model is unique in its ability to differentiate into both proximal small intestine and distal colonic lineages, enabling a comprehensive assessment of viral impacts across distinct regions of the gut.”

Organoids with both intestinal and colonic regions are able to better represent the human GI tract compared to other models, resulting in a more “relevant and reproducible platform for studying viral-host interactions.”

“The organoid platform successfully captures key features of human GI pathology, making it a powerful tool for future research to understand host-pathogen interactions better and identify potential therapeutic targets to treat these deadly diseases,” said co-corresponding author Gustavo Mostoslavsky, MD, PhD, professor at BU and co-director of the Center for Regenerative Medicine (CReM).

Intestinal and colonic organoids were successfully infected with either Ebola or Marburg virus, verifying that the virus was able to replicate within the tissue, disrupt key barrier structures, and interfere with the cells’ ability to regulate fluid secretion.

Both Ebola and Marburg infections resulted in “rapid and substantial transcriptional reprogramming,” identified by changes in a variety of markers, including inflammatory and metabolic pathways. The team used bulk RNA sequencing to clarify unique responses to infection by each cell type in the intestinal and colonic tissues. Viral infection disrupted key signaling pathways involved in ion and fluid transport in the gut and damaged the structure of the gut lining.

There was also significant dysregulation in genes involved with the apical surface structure and tight junction integrity. Morphologically, they found apical damage at the surface of the cells and disruption at cellular junctions in the epithelium. The researchers surmise that this epithelial disruption may help explain how Ebola and Marburg cause the fluid loss that leads to life-threatening diarrhea and dehydration.

Additionally, infection of the organoids showed a delayed onset of interferon-induced gene expression, indicating a delay in innate immune response of genes that typically aid in the fight against viruses.

“This research enhances our understanding of how filovirus infections damage the gut and identifies potential cellular pathways for targeted treatments,” said co-corresponding author Elke Mühlberger, PhD, professor at BU’s National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL). “It also highlights how useful iPSC-derived organoids are for studying viral diseases.”